Pastéis de nata is the plural form of pastel de nata. It literally means “pastries of cream” in Portuguese. But in Portugal, it means so much more than that. These little custard tarts are a national treasure and a symbol of its culinary heritage.

Dating back more than half a millennium, the pastel de nata is said to have originated in a monastery outside Lisbon, the Jerónimos Monastery. The invention of this iconic pastry was the result of a confluence of two plentiful ingredients: sugar and egg yolks.

Portugal was a leading world power in the 16th and 17th centuries, and having colonized Brazil in the early 1500s, it had access to over 2,500 sugar mills. In addition, Portugal was one of Europe’s largest producers of eggs. Peasants would often donate some of their hens’ production to local churches and monasteries.

Used for more than just food, eggs — and egg whites in particular — were useful as a fabric starch, necessary for the crisp white vestments of priests and nuns. They were also used to glue gold leaf onto altars and religious ornaments. That meant a lot of leftover egg yolks.

While the Jerónimos Monastery is the most famous for its pastéis de nata (Indeed, the custard tarts most closely associated with that monastery are given the distinction of being called by the name of the bakery that bought the original recipe from those monks — pastéis de Bélém.), the monks may have gotten the idea, if not the recipe, from other monasteries. Indeed, their religious order was active all over the Iberian Peninsula and is said to have been based at one time in France, where similar pastries have been around since the 12th century.

Even in England, King Henry IV is known to have served egg custard tarts (called by the French word doucettes) at his coronation in 1399. By around 1420, recipes for custard tarts appear in both English and French cookbooks.

But Portuguese pastéis de nata are distinguished by their flaky puff pastry crust, unlike the shortcrust pastry of the traditional English version. Baked at a high temperature, the tops become caramelized, creating characteristic black and brown spots that give them their distinctive look and flavor.

Following the 1820 Liberal Revolution in Portugal, monasteries lost their state funding, so monks had to find new sources of income, which probably led to them selling the tarts to the public. In 1834, religious orders were officially dissolved, and it’s around that time that the monks of Jerónimos sold their recipe for pastéis de nata to a nearby sugar refinery.

Three years later, the owners of that refinery opened Fábrica de Pastéis de Belém specifically to sell the pastries. That shop is still open today and is the only official place to buy pastéis de Bélém, although the generic pastéis de nata can be found throughout Portugal and in Portuguese bakeries around the world. In Lisbon, the little tarts are served in nearly every cafe and pastry shop, usually warm and fresh from the oven with a cup of coffee or espresso.

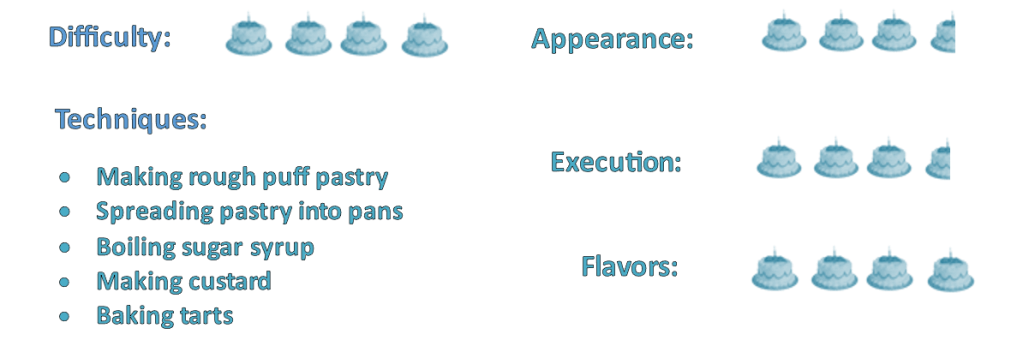

While it may be debated how authentic Paul Hollywood’s recipe is, it certainly provided a challenge for the contestants in the Great White Tent. Noel specified that they should have a “crispy, firm base and a perfectly set, smooth custard.” Paul’s version uses a rough puff pastry, and the bakers had a pared-down recipe. Some struggled with the lamination, others produced a custard that was too solid, but Yan’s was nearly perfect!

The method for making custard for pastéis de nata is different from any other custard I’ve made. Rather than whisking sugar with the egg yolks before adding hot milk, the recipe calls for the sugar to be dissolved in water and boiled to thread stage (223-234°F), then whisked into the milk, which has been thickened with flour over low heat. The hot milk mixture is then whisked into the egg yolks. Upon researching, I found the reasons for this technique are that it makes for a higher sugar content, which gives the custard an “oozier” texture, and it helps to stabilize the custard, which is important given its short baking time in the oven.

To achieve the characteristic swirl on the bottom of the tart, the buttery, layered pastry dough is rolled up like a log and sliced; then the disks of dough are pressed into muffin tins before being filled with custard and baked.

The difficulty I had was determining what size muffin tin to use. The recipe doesn’t specify, so I started with a normal size tin (2¾-inch diameter opening, 2-inch bottom, and 1½-inch depth) but found it difficult to stretch the pastry up to the top. So halfway through, I switched to a smaller tin (2-inch diameter opening, 1½-inch bottom and 1-inch depth). Perhaps as a result of that, I had a lot of custard left over.

Nevertheless, the resulting tarts were smooth and creamy on the inside, crisp and flaky on the outside, with the characteristic swirl of lamination on the bottom. Mine didn’t have as many pronounced brown spots on top, but I didn’t try putting them under the broiler like Yan did. The main difference between the two sizes was the thinness of the pastry and the amount of custard they carried. So if you’re a fan of more custard, go with the larger muffin tins. If you like a thicker (still crispy) pastry and less custard, go with the smaller tins.

I shared some with friends and family, but kept a few for me and my husband to share. With the leftover custard, I picked up some store-bought puff pastry to make more tarts, but the results were underwhelming. If you choose to go that route, make sure to get high-quality pastry dough (Check the ingredients for a high butter content!) and press it as thin as possible in the muffin tins.

You can find Paul’s recipe here, but I’ve adapted it for American bakers below.

Paul Hollywood’s Pastéis de Nata

(Adapted for American bakers)

For the rough puff pastry:

- 1 c. all-purpose flour

- Pinch of salt

- 2 T. unsalted butter, chilled and diced

- 4-6 T. cold water

- 4 T. unsalted butter, frozen

For the custard:

- 7 large egg yolks

- 1½ c. whole milk

- 1/3 c. all-purpose flour

- 2 strips of unwaxed lemon peel

- 1 cinnamon stick

- 1¾ c. superfine (baker’s) sugar

- ¾ c. water

Directions

- To make the pastry dough, combine the flour and salt in a bowl. Rub in the chilled butter until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs. Gradually add enough chilled water to form a dough.

- On a lightly floured work surface, roll out the dough into a rectangle. Grate half of the frozen butter over the bottom two thirds of the dough, then fold down the top third and fold up the bottom third as if folding a letter. Rotate the folded dough 90 degrees and roll it out into a rectangle again.

- Repeat the process, grating the remaining frozen butter over the bottom two thirds and folding as before. Wrap the dough in plastic wrap and leave it to rest in the fridge for 30 minutes. Roll and fold the dough twice more, wrapping it and leaving it in the fridge for 30 minutes after each turn.

- Preheat the oven to 475°F. (Do not use convection heat.)

- Now make the custard: Whisk the egg yolks in a large, heatproof bowl and set aside. Pour the milk into a saucepan and whisk in the flour. Add the strips of lemon zest and the cinnamon stick. Bring to a simmer over a low heat, whisking continuously. Cook for 2-3 minutes until thickened, then remove from the heat.

- In a small saucepan over low heat, dissolve the sugar in ¾ cup of water. Increase the heat and bring to a boil. Continue boiling until a drop of syrup dropped into a glass of water forms a thread (or it reaches 223-234°F on a candy thermometer). Gradually whisk the boiling syrup into the milk mixture.

- While whisking the egg yolks, strain the milk mixture into the yolks. Transfer the lemon peel and cinnamon stick to the egg mixture and cover the surface with plastic wrap. Leave to cool.

- Remove dough from refrigerator and roll out on a lightly floured work surface into a rectangle measuring 8 by 12 inches. Starting at the short end, roll the dough into a tight log and slice into 12 equal disks.

- Using a 12-hole, nonstick muffin tin with each cavity measuring approximately 1½ to 2 inches in diameter and 1-inch deep, place one disk of dough into one of the cavities, swirl-side up. Using wet fingers, carefully press the pastry up the sides, working from the center outwards, until the pastry just pokes over the top. Repeat with the remaining disks. Place in the fridge for 20 minutes.

- Once the custard has cooled to room temperature, remove the lemon peel and cinnamon stick. Pour custard into the chilled, pastry-lined muffin tins, coming to within half an inch of the top. Bake in the hot oven for 15-18 minutes until the pastry is golden and crisp and the custard is bubbling with tiny brown spots.

- Cool the tarts in the muffin tin for 5 minutes, then gently transfer them to a wire rack. They are best served warm and should be eaten within a day or two while the pastry is still crisp.

Discover more from Here's the Dish

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.